In short:

Free cash flow (FCF) represents the cash a company is producing in excess of the cash it takes to maintain its core business and capital assets. Simply put, FCF is the true cash income of a company’s core business which can be used to examine its profitability and value.

This is different from net income in that FCF represents a true cash value whereas net income often includes non-cash expenses or other items that may make it materially different from an actual cash value.

It’s important to note there is no line item on the cash flow statement for “free cash flow”, instead, FCF must be calculated by an investor or analyst. When doing so investors and analysts have a few versions for calculating FCF to choose from, unlevered free cash flow (FCF to all investors), levered free cash flow (FCF to equity investors), or the generic FCF calculation we list below (equity investors).

The most simple formula for free cash flow is:

Key Points

- In simple terms, free cash flow (FCF) represents the cash a company is generating after reinvesting in its capital assets.

- The purpose of free cash flow is to quickly assess a company’s ability to generate positive cash flow.

- Unlevered free cash flow is the most common calculation for free cash flow in DCF modeling and is associated with enterprise value, that is, free cash flow to all investors (debt & equity).

- Levered free cash flow is associated with equity value and represents free cash flow only available to equity investors.

- To properly interpret free cash flow you must understand the components that go into the calculation.

In-depth:

Understanding Free Cash Flow and Why it’s Important?

So why is free cash flow important to understand? The short answer to this is that cash flow is important to know because it is a main component in determining the value of a company. This is because the value of any company is determined by three things, the cash flows of the business, the growth of those cash flows, and the risk around those cash flows.

In addition to this, free cash flow tells investors how much cash the company has left from its core operations to invest in growing the business on its own, paying down debts, paying investors dividends, or other discretionary uses.

Typically, investors will want to see positive and growing free cash flows as this means the business is stable and growing, i.e. appreciating in value. On the other hand, companies that continuously run with negative or declining free cash flows are likely not running a sustainable business and if not corrected will cease when investors stop funding them.

That said, it is not uncommon to see startups have negative cash flows early on as they work to scale their business. This is where the “growth” aspect of cash flows comes in to help determine the value of a company and the things they may need to change to turn cash flow positive.

Simple Free Cash Flow

The most simple means to calculate free cash flow is to add back capital expenditures to cash flow from operations using the formula below:

Formula:

Free Cash Flow = Cash Flow from Operations (CFO) – Capital Expenditures (Capex)

This formula for free cash flow corresponds to equity value meaning this is free cash flow to the equity investors and not to the firm. Where this figure may be useful is in standalone analysis. That is, if an investor wanted to estimate a company’s ability to repay debt, issue dividends, or other discretionary uses.

Why do we use CFO and Capex?

Cash flow from operations represents the cash earnings from a company’s core business. These are repeatable earnings from what the company’s core business is about.

Capital expenditures are subtracted out of the cash flow from operations because, in theory, capital expenditures are not optional. The company must use these funds to maintain their equipment, buildings, software, etc.

Almost everything else on the cash flow statement is “optional” and/or non-recurring or deals with the company’s core business.

*Assumption the financial statements are prepared using GAAP

Example Calculation

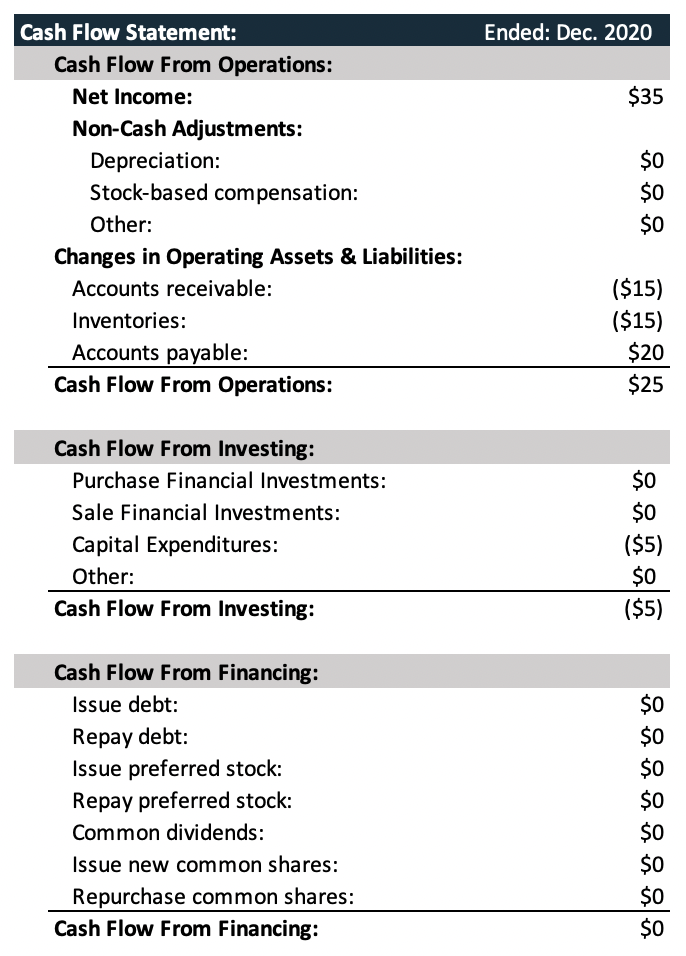

Say we wanted to calculate the free cash flow of a simple business using the simple free cash flow formula from above. If our cash flow statement was as follows:

We can calculate the free cash flow of this business by taking capital expenditure out of our cash flow from operations. Doing so would look like this:

Free Cash Flow = $25 – $5

Free Cash Flow = $20

Doesn’t subtracting out a negative actually turn into a positive? In math yes, however, what we are getting at here is that capital expenditures are a necessary outflow of cash that a company must make in order for the company to continue.

Unlevered Free Cash Flow

Unlevered free cash flow (UFCF) represents cash flow to all investors, that is, both debt and equity investors. UFCF corresponds with enterprise value and is primarily used in discounted cash flow analysis (DCF) when valuing a company based on future (projected) cash flows.

What unlevered free cash flow does is remove the impact of capital structure, thereby making the company more comparable to other company’s while also allowing for the possible adjustment of the company’s capital structure.

When used in DCF, a company’s UFCF will be discounted back to its net present value (NPV). From there, an analyst can then move from the present value of the company’s enterprise value to the company’s present value of equity (i.e. intrinsic value).

The difference between unlevered free cash flow and the free cash flow we saw above is who the free cash flow is attributable to. Since these two types of free cash flows are attributable to different investors, we will need to calculate them differently.

Unlevered free cash flow is more involved to calculate as different items may or may not be included in the calculation depending on the company. However, the general approach is outlined in the formula below:

UFCF = NOPAT + Depreciation & Amortization (D&A) + Change in Net Working Capital – Capex

The reason this formula is different is that we need to account for cash flow that is attributable to all investors (debt & equity). This means we remove the impact of leverage given by debt investors.

Why do we use NOPAT, D&A, and Change in Net Working Capital?

When we calculated free cash flow above, we started with CFO taken from the cash flow statement. CFO starts with net income which is only attributable to equity investors. Since UFCF is attributable to all investors we need net operating income attributable to all investors which is where NOPAT comes in.

NOPAT or net operating profit after taxes is a theoretical value that represents the company’s operating profit if the company didn’t pay interest to debt investors but did pay taxes. Essentially, NOPAT is “net income” attributable to both debt and equity investors.

Once we have our new “net income” we need to add back non-cash expenses typically this is at least D&A. Since D&A are not true cash expenses, we must add them back. This was already done for us above in CFO when we were calculating FCF.

Next, we include changes to net working capital because in order for this value to change the company must either spend or receive money. For example, if net working capital increases, this means the company’s assets increased and in order for that to occur the company must have spent money meaning our cash flow went down -or vice versa.

Finally, we factor in Capex for the same reasons we did above.