In short:

Operating cash flow (OCF) represents the cash generated by a company’s core business operations over a period of time, which can be used to evaluate a company’s profitability. OCF is different than net income as OCF represents true cash inflows/outflows where net income often includes non-cash items.

To account for these differences, OCF (found on the statement of cash flow) begins with net income (from the bottom of the income statement) then adds back non-cash expenses and adjusts for changes in net working capital. The result of these adjustments yields the OCF for the period.

Key Points

- Operating cash flow (OCF) represents the cash generated by a company’s core business operations.

- Operating cash flow is the first of the three sections on the statement of cash flow, it is followed by cash flow from investing and cash flow from financing.

- The process to calculate OCF is to start with net income, then add back non-cash expenses and account for change in net working capital.

In-depth:

Understanding Operating Cash Flow

The value of operating cash flow (OCF) is that it provides a clear depiction of how a company’s core business is operating. That is, since OCF is a true cash figure we can see just how well a company is performing.

While net income is important and a main item in calculating OCF, the two items are different. Since net income can include non-cash items, we cannot get a very clear picture of how well a company is actually doing. For example, a company may appear to have a low net income however may actually have a high OCF because the company has high depreciation and amortization (D&A) expenses.

D&A are non-cash expenses, this means they reduce net income but don’t actually cost any cash money in the current period and therefore don’t impact the cash inflows/outflows of the company. It’s important to account for things like this because at the end of the day cash is what you get paid with and what a company is valued on.

Walking Through Operating Cash Flow

Calculating operating cash flow is one step in “linking” the three financial statements. This is because the bottom figure on the income statement “net income” is the beginning line item on the statement of cash flows and the starting point for calculating operating cash flow.

Like we mentioned above, at this point, we need to adjust the net income figure. From a high-level view, there are three main sections to calculating operating cash flow. They are net income, non-cash expenses, and changes in net working capital.

While the three main sections of operating cash flow are not debated, the line items within them can be debated depending on who you are talking to and the use case.

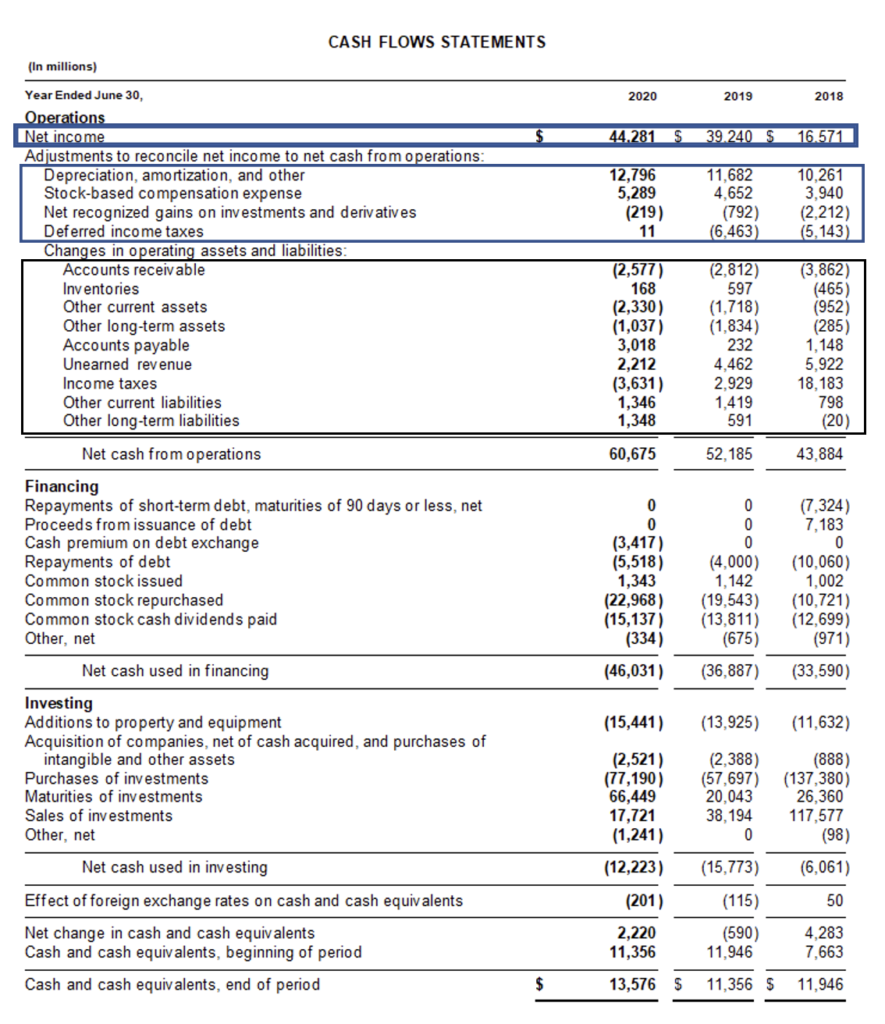

To help make sense of this, we have included a cash flow statement from Microsoft where we have outlined the three main sections.

- Net Income: This is the same net income from the bottom of the income statement and is the starting point for our adjustments.

- Non-cash Expenses “Adjustments to reconcile net income to net cash from operations”: These items include:

- Depreciation, amortization, and other: This is used by accounting to recognize some of the value of assets that are being used over the time period but it’s not actually a cash cost.

- Stock-based compensation: This is not paid with actual cash but rather by the issuance of additional stock

- Net gains on investments: Could come from hedging currency risk for its products/services

- Deferred income taxes: Comes from differences in account for financial statements and cash taxes paid to the government.

- Change in Net Working Capital “Changes in operating assets and liabilities”:

- These items are taken from the balance sheet and represent the difference between the current and previous periods. The general idea here is that when working capital increases operating cash flow goes down because it took cash to increase the assets within working capital.

For example, if inventory increases it took cash to increase the inventory and as a result reduces cash in operating cash flow.